A Silence Beneath the Spanish Moss

Welcome to one of the most disturbing forgotten cases in Georgia’s long and troubled history. In the summer of 1852, a sprawling cotton estate known as Riverwood Plantation, located sixteen miles outside Savannah, became the epicenter of an atrocity so psychologically complex and morally unsettling that local officials concealed it for more than a century.

What began as a curious disappearance of a prosperous white family ended as one of the South’s most terrifying symbols of role reversal—a brutal reflection of the system it was built upon.

The Vanishing of the Hargroves

The Riverwood Plantation belonged to Thomas and Eleanor Hargrove, their three children, and roughly forty-seven enslaved people. On July 14, 1852, Thomas Hargrove missed a scheduled cotton auction in Savannah. At first, no alarm was raised. Summer fevers were common, and absences easily explained.

But three weeks passed. No letters, no visitors, no news. The family had simply vanished.

A neighboring overseer, William Parker of Magnolia Creek Plantation, rode to investigate. His sworn statement described the scene as “unnaturally quiet.” The fields were being tended. The enslaved continued their routines. Yet there was no sign of the Hargrove family.

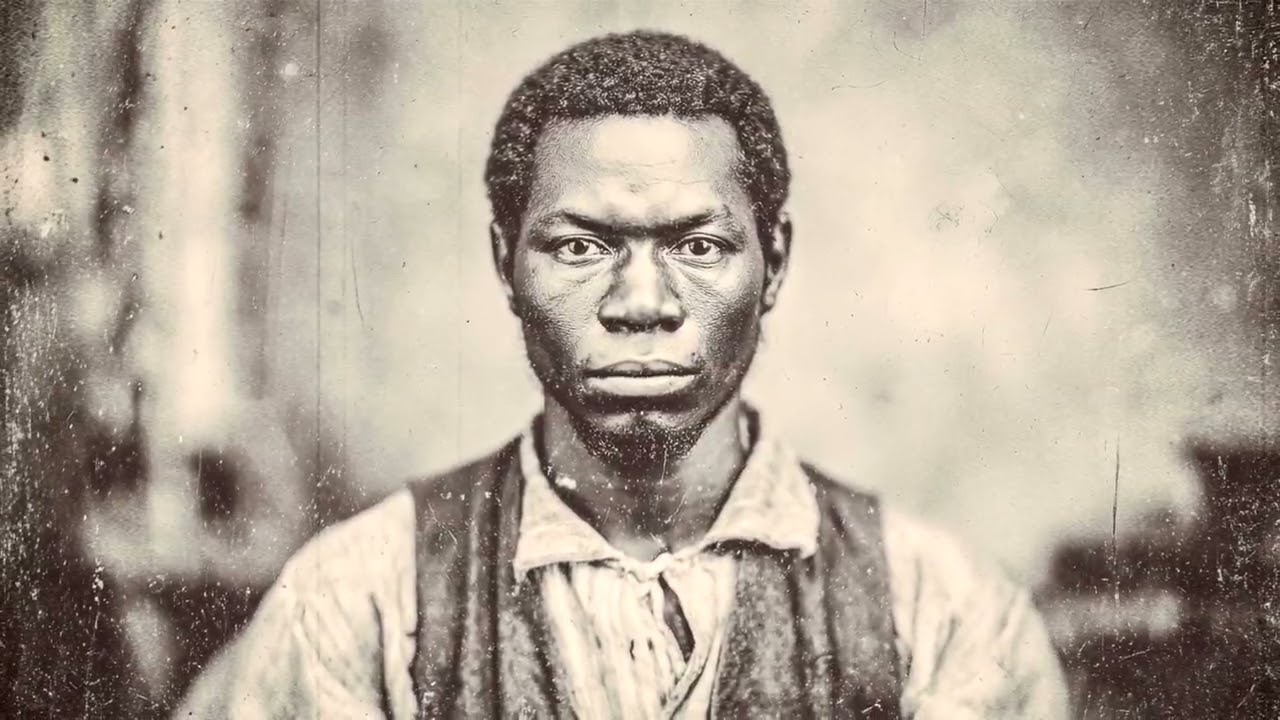

When Parker demanded answers, the laborers deferred to one man—Solomon, a thirty-year-old enslaved craftsman noted in property ledgers as “literate, trained in metalwork, purchased from Charleston 1848.”

Solomon met him dressed in the attire of a house servant, speaking calmly and directly. “Master Hargrove has departed on business,” he said. “He left me to keep the place in order.”

The explanation was impossible—and yet delivered with such composure that Parker withdrew in uneasy disbelief.

A Brother’s Arrival

Three days later, Colonel James Hargrove, Thomas’s brother, arrived from Charleston bearing a letter allegedly signed by Thomas granting Solomon temporary authority over the estate. The signature, later proven forged, prompted Colonel Hargrove to demand a full search of the property.

What they uncovered beneath Riverwood’s grand white façade horrified even hardened lawmen.

The Iron Cages Beneath the Mansion

Like many coastal homes, Riverwood stood elevated on brick pillars to combat flooding. Beneath it was a crawlspace converted into a makeshift cellar. Behind a newly built wall disguised as a root storage chamber, investigators discovered a narrow passage leading to an underground room.

Inside were iron cages—meticulously crafted, each large enough to confine a single person in a position where one could neither stand upright nor fully lie down.

Within those cages lay the decomposing remains of Thomas Hargrove, his wife Eleanor, and their three children.

The county medical examiner, Dr. James Whitaker, determined they had been kept alive for roughly two weeks—starved, given only minimal water, and left to die slowly in suffocating heat.

The cages’ measurements, later analyzed by scholars, mirrored those of the slave-ship holds used during the Middle Passage.

The Craftsman of Vengeance

Evidence soon pointed to Solomon as the architect. For months, he had been tasked with repairing farm tools in the blacksmith shop. At night, he fabricated the iron bars, hinges, and locks used to construct the underground prison.

Fellow enslaved workers admitted that he labored “for Master’s projects,” unaware—or unwilling to admit—they were building his undoing.

When asked why none reported the Hargroves missing, one woman later testified: “Because the fields kept going, and we had never known a day when they did not.”

Solomon had replaced the old order with its mirror image: the enslaved continued working above ground, while their owners languished beneath it, listening to footsteps they once commanded.

The Sheriff’s Account

Sheriff Thomas Blackwood, who led the investigation, wrote privately:

“I have witnessed every manner of cruelty in this county, yet nothing equal to the deliberate symmetry of this act. The design was perfect—an inversion of power crafted with mathematical precision.”

His journal—donated to the Chatham County Historical Society a century later—records sleepless nights and a crisis of faith. Within three months, Blackwood resigned his post and left Georgia.

The Execution

Twenty-three enslaved individuals were implicated in what newspapers vaguely labeled a “domestic uprising.” Seven, including Solomon, were sentenced to public execution.

On September 6, 1852, a crowd of planters and enslaved workers was assembled outside Savannah to witness their hanging.

A planter named Frederick Dalton wrote to his brother:

“They brought near three hundred negroes to see. The man called Solomon looked over them all as if he would speak—but did not. His eyes met ours. I looked away first.”

No last words were recorded.

Erasing Riverwood

Within weeks, Colonel Hargrove sold the estate and dispersed its enslaved population across five states. The new owner, merchant James Mercer, ordered the mansion demolished and rebuilt one hundred yards away. No trace of the original foundation was to remain.

By 1854, Georgia legislators passed the Artisan Restriction Act, banning enslaved people from training in metalwork without a license—a law widely believed to be inspired by the Riverwood case.

Across coastal Georgia, plantation owners began sealing their basements with brick. Officially, to prevent moisture. Unofficially, to keep the nightmares buried.

A Forgotten Horror Resurfaces

The story vanished from public record for more than a century. Files were sealed under “administrative irregularities.” The family’s headstones in Savannah’s Bonaventure Cemetery bore only the inscription: Departed this life, July 1852.

Then, in 1963, courthouse renovations unearthed Dr. Whitaker’s original journal, reigniting academic interest. Three years later, a construction crew discovered a tin box near the former Riverwood site. Inside were notes written in a precise, educated hand believed to be Solomon’s.

The papers, now held in restricted archives, contained sketches of gears, cage dimensions, and cryptic philosophical reflections. One translated passage read:

“Freedom begins in the mind. When a man cannot speak truth, he must build it.”

Historians interpreted the writings as evidence that Solomon viewed his act not as revenge, but as communication—a message to be experienced, not heard.

The Mirror of Slavery

In 1965, Emory University scholar Robert Freeman examined the case in his dissertation Psychological Warfare in Slave Resistance.

He argued that Solomon’s purpose was to make his oppressors feel the precise condition they imposed: “a controlled inversion of humanity—a mirror held up to an institution that denied reflection.”

According to Freeman, the event’s suppression stemmed from its psychological sophistication. “This was not rebellion,” he wrote, “but demonstration.”

The Music That Remembered

Even as official history silenced Riverwood, traces survived in the oral tradition. Musicologist Alan Lomax, while recording Gullah songs in 1934, captured a verse that scholars later linked to the incident:

Iron man made iron rooms down below where no one sees,

Master’s house became master’s tomb, tables turned on bended knees.

The singer, William Johnson, claimed his grandfather had witnessed the hangings.

The Unearthed Dead

In 1969, during highway construction, workers uncovered a shallow mass grave containing seven skeletons on what was once the Riverwood property. Forensic tests confirmed they were the executed conspirators. Three bore signs of post-mortem mutilation—likely intended as deterrent.

Civil rights activists called for memorialization; county officials reburied the remains quietly in an unmarked plot at Bonaventure.

The Haunting Legacy

To this day, no plaque or marker identifies the site of Riverwood Plantation. Suburban homes occupy the cotton fields, but the stretch of undeveloped woodland where the mansion once stood remains oddly untouched. Local residents avoid it, especially at night.

In 2002, a small iron post appeared beside the Hargrove family plot—its origin unknown. Some whisper it marks Solomon’s reinterment. Others call it a monument to untold truths.

Reflections from the Cellar

The Riverwood tragedy endures because it distills the psychology of slavery into a single horrifying tableau: the enslaved craftsman who turned his skill into an instrument of mirrored subjugation.

It cannot be labeled justice, nor dismissed as evil. It is both—a parable of how prolonged dehumanization breeds its own perverse reflection.

Sheriff Blackwood once wrote, “The plantation no longer seems an emblem of order, but of fragile illusion. A place where silence can hide anything.”

His words could serve as Solomon’s epitaph.

The Final Echo

In the end, the Riverwood incident was buried twice—once beneath the house, and again beneath the weight of history. Yet its echoes persist in archives, folk songs, and uneasy whispers along Georgia’s coastal plain.

Perhaps that is fitting. Some truths were never meant to rest quietly.

When the wind moves through the oaks outside Savannah, locals say it sounds like iron shifting underground. And if you listen closely, you might hear it too—the faint rattle of chains transformed into the sound of cages opening, one ghost at a time.